Raw. In the lands of milk & honey, raw means just one thing. Unfiltered. Unprocessed. Just as the cows and bees made it. Raw diamonds mean the same but subtext inverts. Now raw isn't delicious, full fat or pure. It's rough and coarse, not cut or polished. Hardly ever do we see raw frequency response measurements. Otherwise no speakers would sell to any reading audience. Instead we're fed lies of 1/3rd octave smoothing and anechoic conditions to make such graphs look a lot less spiked and wiggly. But the displayed linearity creates wrong ideas about reality. It misleads us about what's required for good sound. We have faulty notions on what that even looks like. Back to raw. The word clearly has nuances. Those cover from pure/untouched to unrefined/coarse with many intermediate values. Civilized folks find coarse and unrefined undesirable. They fancy polished and smooth things as reflections of their self image. Meanwhile refined sugar is bleached, 'pure' white rice stripped off its hull nutrients and glossy grocery apples are dipped in wax. As a Teutonic sprout, I was reared on pumpernickel. Don't dare mention Wonderbread. What effrontery to all that's wholesome. But, a just rough draft lacks corrections, a coarse outline still misses plenty of detail. So raw—au nature, honest, not messed with—routinely goes hand in hand with lack of refinement. By the same token, ultimate refinement could well equal being wholly denatured. Filtering (including crossovers) can smooth things out but in this light also inflict prettifying alterations, insert distance or create certain abstractions. Depending on where you sit, all that becomes a move away from real-as-is-m. Into this gap steps the Japanese aesthetic of wabi sabi. It celebrates life's imperfections. Rather than discard a broken tea cup, a practitioner would re-glue it then treasure the many veins of visible wear. To such thinking, the general notion of plastic surgery is anathema.

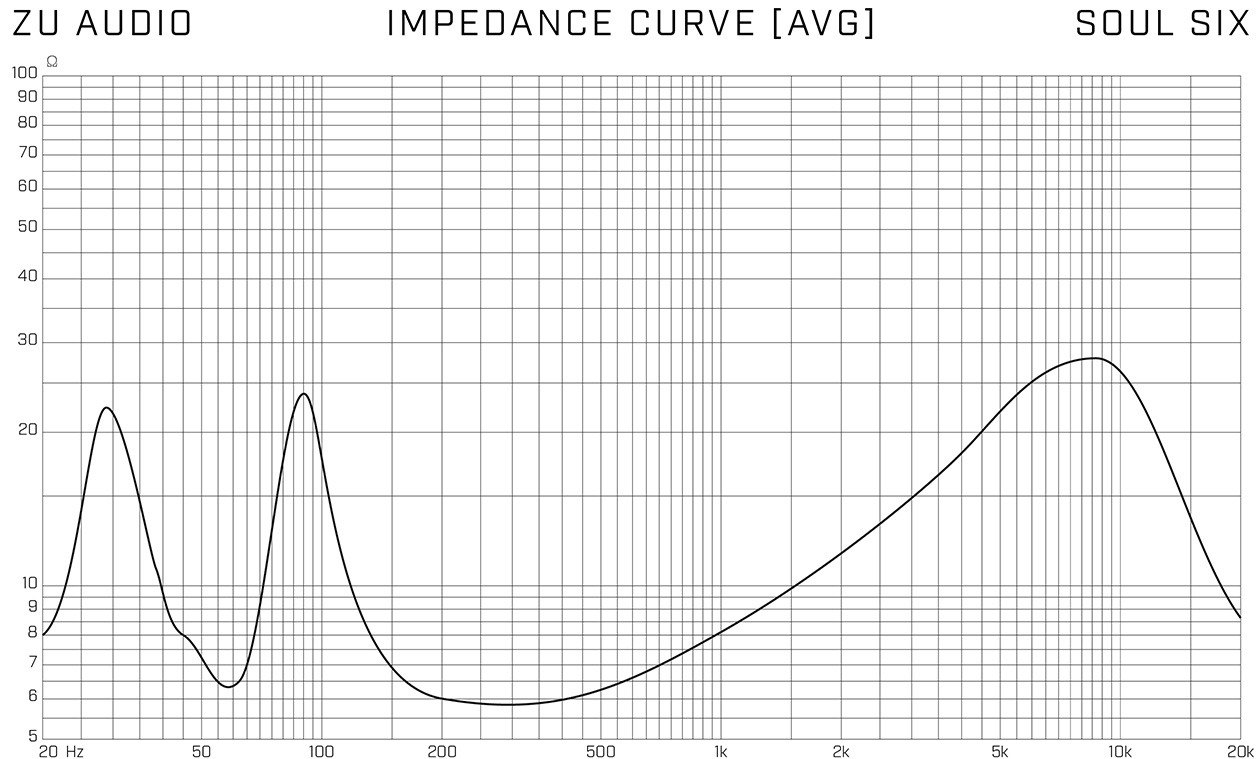

This little stroll down Raw Street seems à propos if, as its concept suggests, the Soul VI prioritizes unvarnished directness. Might that not be accompanied by certain debits on smoothness and refinement? Here thinking folks will look most closely at the 3-10kHz range. It's where the big cone transitions to the whizzer cone, then that to the very narrowly run tweeter. Polish colleagues Cube need three whizzers to linearize and refine the same job without any tweeter assist. Having taken receipt of a burnt-in pair of their v2 10" drivers a week prior to Soul's landing, it was foregone conclusion that the two would square off. To see how the finger ports affect Soul 6's loading, we have Sean's impedance plot. Its peaks center on 38Hz/22Ω and ~80Hz/24Ω. The minimum bass Ω is 6.4Ω/~60Hz into which a regular 20-watt transistor amp will deliver ~30W. Into the peaks it'll do ~7W to now operate at 1/3rd power. Beyond the 200-500Hz trough which doesn't breach 5.8Ω, impedance rises steadily to 28Ω/10kHz, about where the widebander fades out. Here music doesn't make sustained power demands. While claimed 100dB sensitivity might suggest that a 2wpc triode amp suffices, tripling that rating would better account for the Soul's sub 200Hz behavior. To not run an amp at the edge of its power envelope for lower distortion will still want more but also becomes a function of how loud we listen.

Just as the materials promised, this is an easier load than the MkII and Union precursors were because it lowers their Ω peaks. Calling this a nominal 8Ω load as is industry standard just doesn't tell the whole story. Because Zu's design credo goes filter-less like Marlboro Man—the tweeter high-pass is virtually out of band—the Soul 6 can't benefit from any impedance-linearizing circuitry. Control over the response and its loading is entirely down to the widebander's electrical and mechanical behavior and how the cabinet impacts it. Whilst low-power SET without feedback should easily go loud enough, Sean's plot suggests that for best control and amplitude linearity, a 25wpc push/pull for some mild feedback might perform better. As always, your ears are the final arbiter. Zu recommend the 8Ω tap on valve amps with multiple choices. With their cab's 2° baffle lean, the acoustic center's 66cm floor height is said to arrive at standard ear height at 2.75m distance. Experiments with up to 25cm cube risers are recommended. The footer thread inserts are 3/8th on16. Recommended toe-in to start with is face on. "Less will bring a touch of softness." The published bandwidth figures expect us to be within 10° of the main axis. Time to tango.

Where looks matter, Zu's filled-grain stain isn't a demure wall flower but come-hither minx. Ultra smooth and to the touch glassy, I'd never seen wood grain treated thus. Photos do it no justice. Whoever works Zu's paint booth is a prince of the trade. Ivette applauded without prompting. That rarely happens. Usually it's yawn at best or else undisguised diss. No doubt, automotive lacquers are a fine thing. I've had my fair share of custom-lacquered Zu. But being able to see the grain embedded in candy color cut flush as though by blade… in my book that was a whole new level of cool indeed.

The finger ports are called thus because they're about the length and width of an index finger though without preceding tubes or chambers, they really aren't traditional ports, more decompression vents.

The finger ports are called thus because they're about the length and width of an index finger though without preceding tubes or chambers, they really aren't traditional ports, more decompression vents.

Plunked down where speakers in this room go, toed in to see no sidewalls, pug-nosed footers as shown, hitting 'play' already netted good levels at 46dB below 4V unity gain because Goldmund's Job 225 in the rack just then adds 35dB of voltage gain. Now this speaker took off with a very light foot on the gas. The overall profile delivered on Sean's brief without loss in translation. Out of the gate this was very big gutsy sound of excellent imaging and depth layering with unusual dynamic responsiveness. Most competitors need horns to keep up. I had 40-ish bass without trying and high detail retrieval. In trade for overall sonic density, I didn't have the usual air(s). That downplayed ambient recovery of treble fades. On that score, higher heels seemed in order to elevate tweeter/whizzer axis to ear level. I'd repurpose two Artesanía Audio amp stands from downstairs to create the desired lift without interfering with the recommended gap height.

The tonality was baritone in nature. Piano sounded fabulously majestic and massive no matter the recording. Yet Mark Eliyahu's wispy spiked fiddle was unnaturally heavy quite as though its panels had grown thicker. The same held true for female voices. They came across as too masculine. On Mike Massy's Naseej album with the brothers Khalifé on cello and piano for example, Fadia Tomb El Hage's voice sounded too similar to Mike's. She sounded too chesty and male. The extra mass which Zu's 10.3" driver so convincingly hung on piano, cello and male voices—Turkey's Rubato quartet sounded extra splendid because of it—felt a bit too masculine on lighter violin and female voices unless those were power belters like Brazil's legendary sambista Alcione. That's why I called the core tonality baritone. I'd have to see how amp swamps and height changes might affect that performance aspect. Whilst stage height wasn't gargantuan, vocals for example centered on the front-wall/sloped-roof seam a good bit above the speaker tops. There I had no real complaints nor on general tonal weight, overall scale, intensity and aspirated dynamic contrast. What for my type music still wanted fine-tuning was overall tonality. But then these were first impressions so early days. Recording a raw first take simply is instructive should prolonged exposure or hardware changes shift it considerably. That one can only gauge if one remembers how it all began.