|

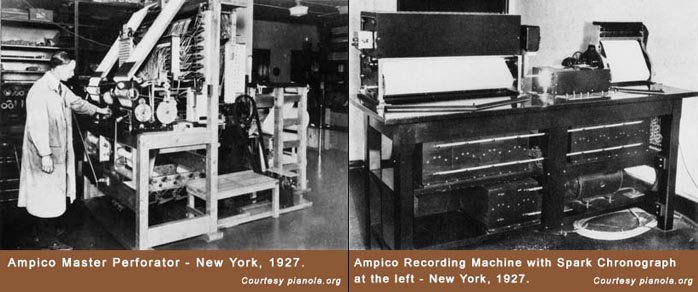

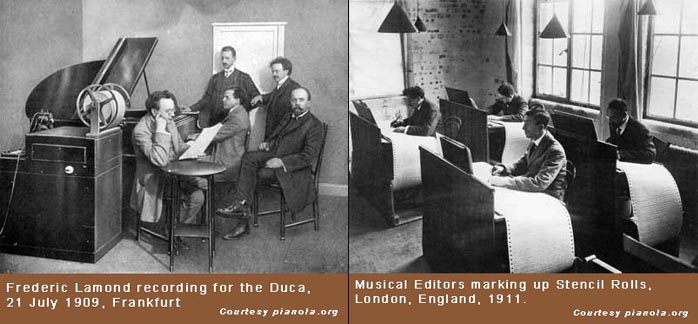

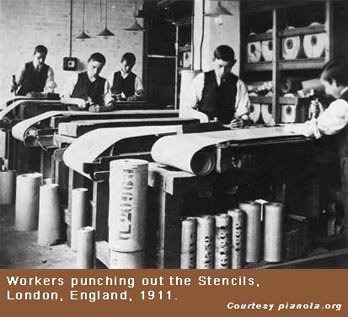

This is partly due to the way the recording was done. The so-called recording was not the kind of recording that we understand today but simply a personal annotation in text, numbers or any graphic codes the recording technician had formulated for his or her own facilitation. The recording engineer was nothing more than an ear witness. While note duration and pedaling could be accurately annotated, strength of the touch was not. This information was obtained by a musician/technician annotating the score while the recording artist played. Whether a recording finalized in the form of a piano roll is a true representation of the vitality and immediacy of the original performance has since become the industry’s as well as the audience’s paramount concern.

|

|

|

|

A/B demonstration recitals by illustrious pianists of the day thus became an important feature of publicity, which happened to recruit a large number of converts and sold a lot of reproducing pianos.

As a music lover of the computer age, we are fortunate in the sense that piano rolls can be perfected in any conceivable ways. Historical rolls can be accurately duplicated without loss of quality and choosing the right reproducing piano—or rather finding a well-maintained or thoroughly restored reproducing piano—is critical.

|

|

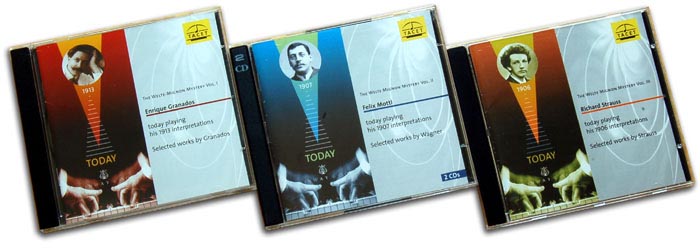

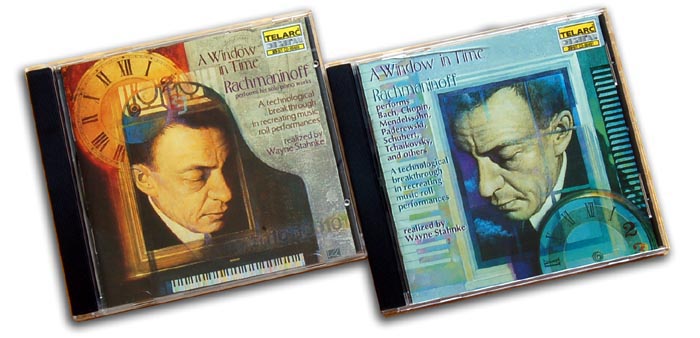

The Welte-Mignon push-up used in the German Tacet releases of The Welte-Mignon Mystery Vol. 1 - 3 [Tacet 135/137/139] has only 0.5% speed fluctuation and is probably the lowest. The piano they used was a Steinway D concert grand and the sonic quality is superb. Trust me, the piano can make a big difference. Let me cite Rachmaninov’s Ampico recordings as a case of study. His complete thirty-five Ampico recordings have been realized on compact disc at least twice: first on Decca [425964-2/440066-2] and then Telarc [CD80489/CD80491]. Prior to that, seven excerpts have been released as a compilation with other pianists’ piano roll recordings by Newport titled The Performing Piano I & II [NC60020/NC60030].

Track for track they should be the same recording from the same piano roll master. However, they all sound different. The piano used in the Newport recordings was an original 5’8” Knabe Ampico B reproducing piano. |

|

|

| The piano used in the Decca albums was a 9’ Estonia. The Telarc albums transferred all the piano rolls into computer data (thus getting rid of the pneumatic valve noise) and re-performed on a 9’6” Bösendorfer 290SE computer-reproducing piano. This one offers the best details and the most exquisite timbre. |

|

| Talking about speed fluctuation, I’m surprised to find that the same piece of music ends up with different duration on the three labels, with discrepancy as big as more than 1 minute for Liebesfreud (Decca 5’51” vs. Telarc 6’54”). In fact, there’s an explanation to that. The technician of the Telarc project, Wayne Stahnke, not only designed a special scanner to obtain accurate imaging of the continuous piano rolls and converted them into computer data files but also thought of a perceptive approach to playback speed. Of the 35 Amipco piano rolls made by Rachmaninov, 29 also existed in audio recordings as 78rpm vinyl. Tempo-wise, these are more reliable than the Ampico rolls. |

|

With the understanding that Rachmaninov was famous for his conviction that there’s only one best way to play any given piece and he always played the same composition at the same tempo from one performance to the next, Wayne reconstructed the tempo and rubato based on the audio recordings. That leads us to the most crucial deciding factor of a reproducing piano recording: the technician.

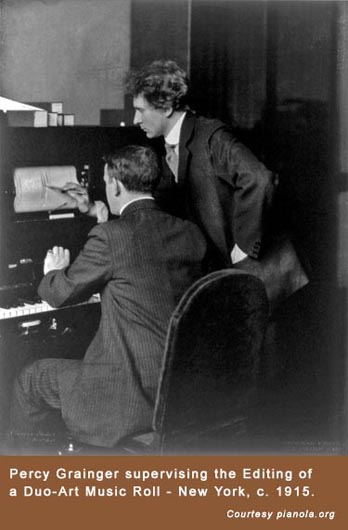

He or she is the one responsible for notating the performer’s every technical nuance and musical expression. Grainger said that the Duo-Art represented him "not as he played but as he would like to have played". (Aeolian, the Duo-Art company, did invite Grainger and other pianists to supervise the editing of their own performances though.) |

|

|

|

If that seems to suggest that the technician can out-perform the performer, well, that’s probably true. In fact, an experienced technician with a musical mind can easily perform from the score without the performer. I am exaggerating the possibilities but this is exactly the skeptic’s handy reason for distrust. But once you think about the modern day recording, the same kind of editing and beautifying jobs are done to most of the commercial recordings. Even so-called live performances get manipulated sometimes. The piano roll technician is doing the same kind of cutting and splicing just to correct inaccuracy. And again, like gramophone records, the recording artists of piano rolls had to sign their consent before a new piano roll was released, to testify its validity and authenticity.

In addition to the normal piano solo, this 2L new release of Grieg and Grainger re-performances has two world’s firsts for the recording industry as far as I know. First, piano rolls combined with live orchestra in a concerto and with violinist in a violin sonata; second, piano rolls realized in multi-channel SACD and Blu-ray.

How does it sound to different ears? Our panel of ear witnesses is at the ready. Find out more as we compare notes through different formats:

• Stereo download and stereo SACD/Blu-ray with Frederic Beudot

• Stereo CD with Joël Chevassus

• Multi-channel SACD/Blu-ray with David Kan

|

|

|

|

|