|

This review page is supported in part by the sponsor whose ad is displayed above

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

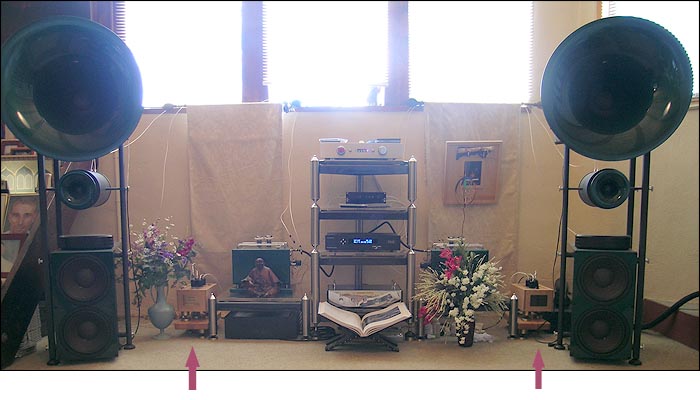

| Reviewer: Srajan Ebaen Source: Audio Aero Prima SE; Accustic Arts Drive-1 Preamp/Integrated: AUDIOPAX Model 5 Amp: AUDIOPAX Model 88 Speakers: Avantgarde Acoustics Duo Cables: Crystal Cable Reference complete wire set of analog and digital interconnects, speaker cables and power cords; Z-Cable Reference Cyclone power cords on both powerline conditioner; 2 x Stealth Audio Cables Indra analogue & Sextet S/PDIF cable Stands: 2 x Grand Prix Audio Monaco four-tier Powerline conditioning: BPT BP-3.5 Signature Plus; Velocitor; Velocitor S [on review]; Quantum Symphony Pro [on review] Sundry accessories: GPA Formula Carbon/Kevlar shelf for tube amps; GPA Apex footers underneath stand and speakers; Walker Audio SST on all connections; Walker Audio Vivid CD cleaner; Furutech RD-2 CD demagnetizer; WorldPower cryo'd Hubbell and IsoClean wall sockets; Musse Audio resonance dampers on DUO subs Room size: 30' w x 18' d x 10' h [sloping ceiling] in long-wall setup in one half, with open adjoining living room for a total of ca.1000 squ.ft floor plan and significant 'active' cubic air volume of essentially the entire (small) house Review component retail: $2,995 without power cord, $450 for optional matching stand |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

As regular readers here and elsewhere already know anecdotally and owners from personal experience, Lloyd Walker is one of the more colorful but bullshit-adverse artists in our small cottage industry. This aversion against smelly manure stems from a long career in controls work on nuclear reactors and petrochemical plants. Such plants suffer no fools, period. The artistic part comes from a nearly maniacal commitment to better sound. It translates as a willingness to tackle challenges like a lock-jaw bulldog and grapple with new ideas even after a product has been launched. It also includes experimenting with solutions whose exact workings he doesn't fully understand. Take his passive power line conditioner called the Velocitor. It relies in part on QRT or Quantum Resonance Technology, proudly credited on the engraved brass plaque with its initials. The QRT module is licensed from Bill Stierhout of Quantum. It also finds itself built into Kiuchi-San's Combak/Reimyo conditioner while QRT-treated boards show up in NordOst's Thor conditioner which was jointly developed with IsoTek of England. Asked how QRT works, exactly, Walker relies on his grim distaste for poppycock. Rather than pretending, he'll tell you plainly that he doesn't know - though he could regale you with a few theories if you really insisted. "Just listen and you tell me whether it works or not" is a far more likely retort. While he's at that, he'll also tell you in no uncertain terms that the module benefits from serious tweaking and modifying and is merely one ingredient of what makes his Velocitor different. |

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| In fact, "the devil's in the details" is Lloyd's favorite non-Hindu mantra. As such, he's one restless character. He is never done, especially when word comes down the pike that a new product introduction elsewhere might challenge | |||||||||||

| one of his. If he trusts the ears that say so, he'll buy that product or go out of his way to try it somewhere. If he finds that it indeed beats his own or merely comes uncomfortably close, he'll curse quietly as though it was a personal attack on manhood and design acumen. Then he won't rest until he's figured out how to improve his own Walker Audio equivalent to gain the necessary audible advantage. Once he's managed, he'll let you know, too. More than that, he'll lean on you until you cave in and give the thing a listen. Seeing that I already owned one of his Velocitors, that's how today's review came about, too. Lloyd had experimented with the RF detection coil inside the Velocitor. The Mapleshade cables he fancies and sells run an active bias on their shields. So do certain Audioquest designs for their dielectric. In parallel to Bill Stierhout who was experimenting along similar lines, Lloyd decided to put an active bias on the field coil circuitry. After the necessary dialing in, he sprung the hotrodded Velocitor S on his wife Felicia. He replaced the prior Velocitor in their video system with the tweaked one. Her reaction told him all he already knew. "It's huge!" I was next in line to find out. You see, once you're part of the extended Walker family by owning his stuff, it's like having a mad genius inventor for an uncle. In Walker's case, such upgrades are always priced fairly. Present owners are guaranteed instant access and quick turnarounds to stay with Lloyd on his cutting edge. Unlike dealing with larger firms who might be less prone to ongoing refinements, the Walker magic is one of endless questing for incremental improvements. |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

The Velocitor recipe thus far has meant a solid Maple enclosure 10" x 7.25" x 7.5" and a complete absence of lights and switches. It also has meant a tension-fitted set of 5 miniature Walker Audio Valid Points (5/16" tall) and lead-filled Resonance Control Discs inside the box for a deliberate attenuation of powerline-induced mechanical resonances. (Kimber Kable's Palladium power cords with their midriff barrels seem similarly directed at resonance issues.) A complex wiring scheme connects each of the six top-mounted outlets back to the IEC. This is done via deep-cryo'd parallel ultra-pure silver/copper runs rather than tapping off a central bus bar distribution rail as is popular elsewhere. (I'm told wiring up the Velocitor is one royal pain in the arse.) There's Jena Labs deep-cryo'd Hubbell-based outlets with a proprietary metallurgical contact formula (Caelin Gabriel of Shunyata too has Hubbell-sourced outlets that incorporate specified refinements). There's the aforementioned RF detection coil and the QRT oscillator/transmitter. There's a hard-mounted set of external brass/lead Valid Points below the Velocitor. Ideally and as chez moi, those should couple to the optional butcher-block Maple platform, itself decoupled from the floor by another set of hard-mounted points. A spare disc is placed atop the platform between the three footers of the Velocitor. Add a brass grounding post and the new active bias. Voilà - a passive power line conditioner without any of the usual filters, chokes, capacitors, isolation transformers, power rectification or regeneration, surge protection, LEDs, voltage stabilization or what-have-yous. According to Walker, it's all bad for the sound, in some out-of-fashion or another. |

|||||||||||

| The QRT module creates a field effect that affects the upstream power distribution for a certain distance. To fairly test the Velocitor, it needs to be unplugged whenever a comparator is inserted. Otherwise the latter rides on the Velocitor's coat tails and benefits from the QRT's electron resonance treatment. Before you, ahem recoil from such statements -- perhaps inured from the current AA threads about Golden Sound's Intelligent Chip for CD treatments --remember that Walker makes no claims for how QRT works. He simply states that he's tried it, that it's clearly audible (and visible on video) and that it can be improved upon over how Quantum has implemented it. Once you add into this picture the considerable expertise involved to design and build one of the most highly accoladed turntables ever -- the Walker Audio Proscenium Gold previously featured in these pages -- the voodoo portion of the Velocitor's operation and ingredients recedes into the | |||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| background. Incidentally, explanations for how Bybee devices operate are surprisingly similar to QRT. Far more important to audiophiles than theories is naturally the question: Does this stuff work or not? If so, how well does it work? As Linnman's recent foray into passive power bars showed, many Japanese companies like Audiorepas, Chikuma, Furutech, Orb and Oyaide -- but also Gryphon Audio of Denmark -- favor the filter-less passive approach. They focus on power distribution rather than conditioning/filtering and nearly always mate that to apparently overkill mechanical construction. Conceptually, active powerline filters become part of the power supplies of whatever components are plugged into them. This could cause unforseen interactions that second-guess and potentially compromise the intentions of the designers of said components. Remaining with a passive approach eliminates the potential for such compromised interactions, between a conditioner's active componentry and those in the power supplies of the connected equipment (and it should also avoid current/voltage shifts and associated AC phase errors). Using a single power distribution source for one's entire system eliminates line-induced ground differentials and is thus favored by many. Another consideration is how the presence of some remaining subliminal noise might actually be beneficial like dither is for digital; like tube noise might contribute to certain sonic effects of valved circuits; like minor tape hiss isn't always merely negative but can also create an unexpected illusion of additional space. If so, categorically eliminating all AC noise to level zero as though this were the Holy Grail could entail some surprising consequences not necessarily all benign. On this subject, Linnman's findings (which include prior experiences with active devices as championed by Burmester and isolation transformers by way of Ensemble) can be paraphrased as follows: The silence created by passive resonance control is very different from that achieved by massive active filtering. The former is a live and present silence, the latter a dead silence of absence, damping and suppression. Those in accord with this view would tell you that what is suppressed beside grunge and noise is also musical life, energy and spontaneity, otherwise expressed as micro and macro dynamics and speed. There are parallels in speaker construction with those who favor a tuned cabinet over one poured from concrete. There are parallels even with speaker stands, between the dead-knuckle variants on one end and the deliberately resonating ideal of StarSound's Caravelle model on the other. One scheme endeavors to kill vibrations by damping them, the other aims at releasing vibrations via grounding. Perhaps there are further parallels with the resolution-for-resolution's-sake approach? Lowering the system noise floor as influenced by the AC power grid is a good idea in theory. But if in the process, something vital gets stripped away as well, more might be lost than gained. This could relate directly to what one expects from the playback experience. If you focus on a merely sonic approximation or recreation of the live event (something I believe is completely impossible and thus a fool's errand), then a singular pursuit of minute detail retrieval could become priority numero uno. If an emotional approximation or recreation of the live charge was your intent, then the transmission of energy would gain precedence. This might result in two entirely different results. They could cater to two different ways of listening. Neither is wrong and both will have admirers and detractors. In fact, Caelin Gabriel of Shunyata Research has coined two utterly brilliant terms to describe these dissimilar actions: NoiseKillers and PaceSetters. |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| The Velocitor S clearly operates in the second class. As such, it's just as brilliantly named. It acts as an arterial declogger, accelerator and thus caffeine infusor. Where my BPT BP-3.5 Signature Plus is a noise killer and excels at image density, mass and damping, the Velocitor is a pacesetter. It excels at speed, dynamics, jump factor and release. I can't necessarily tell you that one makes the system quieter than the other. If something of the sort were measurable, my listening abilities can't discern it. What I can tell you? When I reduced my system's box count to run off just one 6-outlet Velocitor (by replacing my Zanden DAC/Audiopax pre combo with the Audio Aero Prima SE DAC/pre), I could compare my original Velocitor against the new S version against the BPT. The balanced power unit sounded denser, slower, darker, somewhat blunted and rhythmically restrained. The nature of this effect was similar to how an underdamped tube amp behaves into a poorly matched speaker load. Things get slower, darker, thicker, heavier of foot. The original Velocitor was more agile, more energetically lit up and sparkly. Inserting the Velocitor S increased focus, clarity and soundstage size. Even more impressively to me, it also seemed to affect tonal color temperature. Somewhere in this double action of focus and color, the Velocitor S introduced a heightened effect similar to image density. However, its nature was noticeably different from that exerted by the BPT. The latter's density derives from mass, grunt and a sense of displacement. The Velocitor's is rooted in energy that doesn't stick but let's go rapidly. It's as though the balanced power unit suffered a bit of inductive hold by comparison. A side effect thereof was the appearance of bigger BPT bass. Listening closely, bass notes didn't seem to let go as quickly, hanging over a bit. This elongation created an impression of more quantity - but now I'm a bit suspicious about the effect. |

|||||||||||

| Another way to describe the general difference of flavors would be to point at the gains (and not parallel losses) which passive preamps can bestow: immediacy and directness. Compared to active preamps, one commonly trades for less body and an overall leaner, more transparent presentation. Echoes of these generic parallels seem to also exist between Walker's passive approach vs Chris Hoff's active approach (which in the BP-3.5 includes a Plitron balanced isolation transformer, capacitive filtering, ERS applications and more). Depending on preamp execution, both active and passive approaches can simultaneously add and take away. The best of them (and in how they interact with a system) only add and don't subtract. Admitting once again that one never knows where the exact center line really lies, the BPT seems to add density and weight but subtracts speed. The Walker adds speed and thereby rhythmic | |||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| elan. I don't believe it subtracts anything. However, by not adding body, it might seem to subtract it by comparison to the transformer-coupled unit. The real surprise was the unexpected action of the new Velocitor's S factor. To my ears and to remain with generalities or flavor camps, it seems to be an ideal marriage of "passive preamps + tubes". There's the speed and openness of passives and the energy and dimensional focus of well-implemented tubes with their micro-dynamic reserves. Whether the S version does add a bit of body or really tonal color or whether it instead achieves this effect primarily by increasing focus and scale is hard to say. Still, the sense of increased corporeality is clearly present. Because of its innate reflexes, you might suspect the Velocitor to be slightly edgy in terms of transient definition. It's not. Transients are explosive and well-defined but not chiseled or exaggerated. They simply seem more precise than the BPT's because they let go so rapidly. I wager a guess that the fine balance on tap here is partially a function of running cryogenically treated silver and copper conductors in parallel (and in a predetermined ratio to combine specific attributes). Be that as it may, the velocity function of this unit doesn't come at the expense of zippiness, stridency, hype or forced excitement. In that sense, it's not an emphasizer but a liberator. As my system has changed -- and likely my tastes -- the Velocitor S' passive approach with its combination of mechanical resonance attenuation/tuning and the mysterious but clearly efficacious QRT treatment has rather eclipsed my previous work horse, the BP-3.5 Signature Plus. Running the system off two Velocitors allows me to separate analog and digital or power the current-heavy Duo subwoofers from one and the puny-draw remainder of the gang from the other (I'm still undecided on how I'll settle down). One thing is for sure - my original Velocitor is going back to Pennsylvania for the active bias upgrade and the review unit is staying put. Our own Mike Malinowski of the Wilson Audio Alexandrias just had his Velocitor upgraded to 'S' status while Linnman in Hong Kong acquired a second unit. Having outright purchased their units to not owe me any publishable comments, both still volunteered brief second opinions [see next page]. Concluding my own findings, the Walker Audio Velocitor S reminds me of Serguei Timachev's Indra cable. Like the Indra, the Velocitor doesn't do anything in the frequency domain. It doesn't add bass, sweeten up the midrange or contour the treble. It's not a tone control. Like the Indra, it eliminates something instead. What the Velocitor removes is a clear sense of restraint and immobility plus some surface texture fuzz. It's as though its presence in the system equated to dropping some subliminal weights. This removal of restraints then liberates something else. Just like people look younger, healthier and fitter when their frames carry no excess weight, so the music plugged into these Walker units gains zest and vitality and an improved sense of timing. In my book (and now that I've heard it with the balanced power unit moved into the video system), that's exactly what I want. While I really don't understand how this works -- e.g. why does even an extraordinary power strip have these kinds of effects to begin with; after all, it's "just" AC -- I clearly hear it. As far as I'm concerned, the Lloydmeister has done it again. He's made an already terrific product better still. The original Velocitor had already garnered one of our Blue Moon Awards. The new version deserves it doubly by going beyond the original performance in easily audible ways. That's typical Walker - to improve something you were already perfectly happy with. Somebody tell that fella to take a break! Just kidding. Can one ever have enough of this type of madness? If you're passionate about audio, surely not. |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||