|

|

|

Album Title: Chopin: Piano Sonata No.2 in B flat minor / Liszt: Piano Sonata in B minor / Scriabin: Piano Sonata No.2 in G sharp minor / Ligeti: Etude 4 & 10

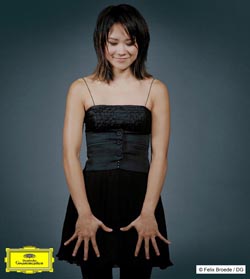

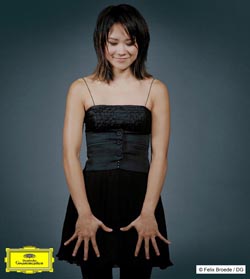

Performer: Yuja Wang, piano

Label: Deutsche Grammophon 477 8353

Recorded: November 2008

|

When news broke last month that Yuja Wang had been named Classic FM Gramophone Young Artist of the Year 2009, I was not surprised. With only one debut recording released and no big piano competition win under her belt—and I mean those really big spot-lit coliseums that send the winning gladiators marching onward to rocketing careers—it’s still obvious that nobody would have deserved that prestigious award more. Icing on the cake soon followed. Her debut recording reviewed here also won the Best Debut CD 2009 Award from International Piano Quarterly, undeniably the most authoritative classical piano magazine. Looks like some unanimous conclusions are drawing already. But first, I have a confession to make.

|

|

|

|

|

When I first heard about this CD many months back from a Chinese magazine, I felt rather indifferent. You’ve probably heard the joke that if you see a young Chinese on the street not carrying a violin case, most likely that young person is learning the piano. With so many Chinese musicians coming and going, it’s hard to keep track especially when the novelty and patriotic factors are wearing thin faster than the new releases they can put out. I was more than happy to pass on this "female Lang Lang". |

|

|

Oh no. That horrible stereotyping was not mine but the magazine’s. How very disrespectful to the artist and her teacher (who also taught Lang Lang); how misleading for me! Many months went by and one lazy afternoon I bumped into Yuja’s album page on DGG's website. Since I was there, I randomly clicked on the first sample track not knowing what to expect.

All it took was a two-minute excerpt of the first movement of Chopin’s B flat minor Sonata and my whole conception about piano playing was changed. I’d never heard Chopin so hot-blooded and expressive. Only two minutes with low-fidelity sound coming through the 1W built-in speakers on my LCD monitor were enough to jerk me out of my indifference or ignorance.

|

I must digress here and tell you about another Chinese magazine. This time it was an interview with a world-famous Italian pianist during his Hong Kong visit earlier this year and his very first recital there. Mind you, it’s a thorough and professional interview. I'm simply being over-sensitive. Towards the end of the interview, the dialogue shifted focus onto young pianists of today who, in the maestro’s mind, lack individuality. The interviewer threw in a gratuitous comment that young pianists nowadays possess only technique but lack personal touch and tone colors. The maestro contentedly agreed and elaborated, "Most Chopin interpretations these days are too polished and harmonious. They desperately need more untamed tension." (The original interview was presumably conducted in English but the published text was in Chinese. Some terminology might have gotten blurred here in the double translation but the crux of the content shouldn’t deviate much.) I felt very sad after reading that. Instead of making artistic advancement, the maestro had fallen back into artistic protectionism. I am keeping all his Chopin LPs though I never noticed any untamed tension. He'd been my idol because everyone had said he was good. After all, he'd won the Chopin Competition back then when I was still learning to appreciate classical music. Now I’m glad that I've gained my own mind over the many intervening years and learned to appreciate the untamed tension in Chopin – first with György Cziffra and Martha Argerich, now with Yuja Wang.

|

|

Only this time, the revelation was so uplifting that it uprooted my long-held belief about the art of piano playing. From where I was brought up when I was brought up, music critics put a lot of emphasis on tone colors. Everyone praised the great masters like Cortot, Hofmann, Godowsky, Gieseking, Rubinstein and Michelangeli for their unique tone colors that allowed them to be identified instantly. I dared not dispute that until Yuja. I listened through all her Chopin sample tracks on the DGG website and was utterly thrilled by her bold conception of this frequently recorded work. It was absolutely unique but not about tone color, not from the feather-weight monitor speakers of my computer. That was conception, interpretive strategy. After I had a chance to listen to the actual CD a few times, I was convinced that while tone is not unimportant, what makes an interpretation unique is the performer’s conception of the work. That's about how much emotion and energy the performer can put into the work, how expressive it can become and most importantly, from what angle it is expressed.

In other words, it’s the bigger picture of how well the performer understands and feels for the work and then manages to communicative that. Now I came to understand that tone color, no matter how refined, is just a technique or carrier to convey the message and project the conception. Honing sound to perfection is no different than drilling an acrobatic passage to flawless precision or pursuing hifi equipment for its audiophile traits.

|

|

Without the slightest intention to degrade individualistic timbre and its adherents, it could be viewed as a purely indulgent technical gimmick all the same. Why then is it tradition to universally praise pianists for exquisite tone while the virtuosi (who ironically also possess great tone) are slighted? I know I shouldn’t pass judgment since I haven’t heard any of the great masters of tone colors live. But judging from the recordings I own, I am tempted to say that they have more in common than not. They belonged to the era when lyricism ruled and reformism was taboo. Tone became the game of thrones. I can tell a Fazioli from a Steinway in one minute. But to do the same with the great masters of tone colors? Maybe I could tell Godowsky and Cortot from their eccentric tempi in handling certain repertoire but definitely not from their tone.

Even by today’s standards, to me Yuja is still a reformist. Of course she has both expressive tone color and an incredibly big technique that’s far larger than her physique. But her real strength is the bigger vision – her own conception and determination in making a statement with every work she performs, be it a romantic concerto or virtuoso encore. Like violinist Hilary Hahn whose biggest strength is conceptual (which embraces tone and technique both), Yuja is able to formulate and project her unique vision onto her repertoire.

|

Chopin’s B flat minor Sonata has been criticized for lacking continuity throughout the four movements because they are all rich in musical ideas, strong in personality and therefore somewhat unrelated. If that’s true, Yuja embroidered these many colorful swatches into one magnificent quilt in the most seamless of fashions.

The first two movements are propelled with an untamed tension of happy thrust and tormented counter thrust, of anxiety and consolation at a slightly faster tempo than most. Rubato comes at the expense of emotional wax and wane which never rests nor slows down. Multi-layered stanzaic contrasts are well articulated with imaginative attention to inner voices.

The famous third movement of the Funeral March is refreshingly bright and sunny. Who said it has to be desolate and gloomy? Funerals can be a time of honor and solace. This is that exactly, each step full of confidence towards a brighter future. Suddenly, this unusual manifestation of the Funeral March provides the key to the long unsolved continuity myth.

|

|

|

This positive attitude becomes the perfect bridge between the two preceding movements and the finale Presto. Unlike most pianists’ sudden outburst of torrential emotions that end the sonata in a gust, Yuja’s resolutely rational treatment is adorned with immaculate detail and a highly contrasting dynamic range that add depth and dimension to this descriptive movement. Incredibly, she does all that at a speed that’s as fast as anyone's yet you never sense any impetuosity.

Liszt's B minor Sonata is perhaps the most emotionally laden in the entire canon of piano literature. Musicological speculations on the true meaning of the work range from a tale of Faust and Mephistopheles to an allegory of the Garden of Eden and Man’s first disobedience or soul-searching autobiographical fantasy to simply a piece of absolute music too advanced for its time. Any piece of music can be analyzed down to the bone yet what matters most is the response in the listener's heart. This sonata speaks to me as ongoing conflict between religious obligation and earthly desires which haunted Liszt ever since he was a young man. In other words, I completely buy the concept of autobiographical fantasy. Ever since watching the Fonteyn-Nureyev collaboration using the sonata in their balletic interpretation of La Traviata, the romantic Recitativo and Andante sostenuto always conjures up images of a love scene and death bed in my head.

|

|

Exploring the multiple recordings of this 19th-century keyboard colossus in the 1999 Winter issue of the International Piano Quarterly, Mr. Philip Kennicott examined more than 60 recordings available at that time and classified them into three loosely defined categories to discuss their relative dangers and merits.

"The narrative versions offer sharply characterized episodes and dramatically contrasting thematic materials. The introspective accounts have their centre of gravity in the sonata’s most intimate moment, accentuating the vocal quality of the passages such as Recitativo. The purely musical accounts cannot be easily summarized, but often make statements about the sonata’s structural qualities, its relative modernity… Narratives can become episodic and loosely structured. Personal (introspective) accounts can degenerate into self-indulgence and eccentricity. Purely abstract readings can be too detached and emotionally desiccated."

|

|

|

Obviously I haven’t listened to all the available recordings (there must be more than 70 by now), yet of the 15 or so that I have collected over the years, I don’t really like Richter (too introspective) or Berman and Howard (too rushed both). I admire Bolet, Brendel, Gilels, Feltsman and Sofronitzky and am really crazy about Cziffra, Horowitz and above all, Argerich.

Interestingly, very few female pianists have recorded this behemoth yet more often than not it’s the female pianists who seem to bring out the passionate inner beauty of the work. Apart from Argerich, Jenny Lin, the ‘virtuoso’ from Taiwan, offers another heartfelt reading on BIS. Yuja’s interpretation of the Liszt B minor is nowhere close to "detached or emotionally desiccated".

Her sensible choice of tempo and unregimented use of rubato convey balletic fluidity yet cleverly sidestep rhythmic perversion. The "sharply characterized episodes" such as the defiant Grandioso, the to-die-for Recitativo love scene and the introspectively lyrical Andante sostenuto are "dramatically contrasting".

Throughout, Yuja maintains a center of gravity that traverses movement division. Again, it is the bold conception that makes this rendition a winner and sets her abreast with Argerich.

|

|

|

Her Scriabin Sonata No.2 is just as inspiring. Despite this so-called Sonata-Fantasy being more accessible than the other Scriabin sonatas with programmatic references to a night by the sea in the first movement and a storm in the second, there are still evocative moments that linger with mysticism. Yuja’s resolute approach takes Scriabin out of his self isolation and redefines the romantic vein previously camouflaged under the improvisational mask. Her first movement Andante is the most sensuous and compelling I’ve ever heard. Not even Sofronitzky was this at ease. As for the Presto, I’ll rank her second to my reference, Ashkenazy’s Decca recording whose dynamic contrast is still the most formidable.

|

Yuja has a flair for virtuoso works which exemplify her technical brilliance in the most casual manner. Her two Ligeti Etudes are executed with wit and playfulness. The concert paraphrase of Mozart’s Alla turca by Acardi Volodos is not only inhumanly fast but also the most cunningly articulated, all inner voices singing adroitly, weaving in and out like water nymphs, all bouncing notes flawlessly dotted on the right spots. To be honest, her playing makes Volodos sound grumpy and pounding . On YouTube we’re able to witness more: The Flight of the Bumblebee (not Rachmaninov’s but Cziffra’s dare-devilish version), Carmen Variations (Horowitz), Gluck’s Dance of the Blessed Spirits (Yuja’s transcription after Sgambati) and Stravinsky’s Petrushka. Again, Yuja’s nimble fingers make her Bumblebee faster, lighter and more amusing than Cziffra and Volodos. If you’ve been wondering about her name, Yuja means "feathery delight" (as in delightful mood) or "pleasantly feathery" (as in pleasant weather). These videos are testament not only to a virtuoso of boundless technique but a true musician with real depth. (Don’t miss her Vivaldi Four Seasons on four pianos with Emanuel Ax and friends!)

|

|

|

|

Another rare quality is Yuja’s casual yet graceful stage presence. While we’re growing tired of the other young Chinese pianist who puts on too much facial expressions, Yuja moves every ounce of her expressions into the music. She walks on stage with a beaming smile and bow, sits down and insouciantly adjusts her stool (sometimes flicks her hair), stretches out her arms and immediately commences playing. She doesn’t even bother to take a few deep breathes or close her eyes pretending to focus or summon her energies. There’s music in her at all times. Once her fingers touch the keyboard, her energy seems inexhaustible as if she’s recharging from the piano.

As Yuja’s biography is readily available on many websites, I’m not going to repeat it here. But on the Chinese classical music website Wunderhorn, there’s a collection of interviews which provide us with a vivid portrait of the making of this young artist. The followings are highlights from the many amusing and touching colloquies from the mouths of her mother, her Chinese teachers and Yuja herself.

|

|

- Yuja started playing the piano at four. Her father is a percussionist, her mother a ballet dancer. Young Yuja was naturally attracted to the piano and could practice for hours. Her mother had to tell her to stop to eat.

- She had three teachers before going to Canada on her own at the age of 14. The plan was for the United States but a visa proved difficult to obtain so Canada was to serve as stepping stone. Yuja was recruited as an exchange student to the Mount Royal Conservatory, Calgary.

- Yuja found a home stay family and lived with an elderly Canadian woman. She had to take care of herself running all daily errands from grocery shopping to banking and applying for her American visa and school transfer. She survived the bitter winter but always felt hungry for more piano exercise. She complained that the conservatory was not ‘feeding’ her enough. She learned English fast and became an avid reader of science and philosophy books, which she believed would help her musical interpretation.

- Yuja was admitted to the Curtis Institute of Philadelphia at the age of 15 going on 16. By that time she was already a very independent young lady. Her teacher Gary Graffman is a big fan of Chinese culture, Chinese antiques, Chinese composers and has traveled further in China than Yuja herself. Besides Lang Lang and Yuja, he recruited two other Chinese students at about the same time.

- Yuja wanted to participate in international piano competitions but Graffman’s advice was: "You don’t need that. If you want to plot your path to a musical career, all you need to do is perform." So Graffman introduced his own manager to Yuja. (Graffman was an awesome pianist with many legendary recordings with George Szell and Leonard Bernstein on CBS/Sony before injuring the ring finger of his right hand.)

- Graffman’s tactic was to train her up as replacement soloist. Yuja quickly learned the standard repertoire for concertos and memorized not only the solo but also orchestral parts. She was ready to perform more than 20 concertos (now approaching 30) on a last minute's notice. Since her hugely successful replacement appearances for Radu Lupu, Martha Argerich and Murray Perahia, her fame has spread among conductors and soon she’s being invited to music festivals and her own concerts. Abbado thought very highly of Yuja and called her the most outstanding female pianist since Argerich.

- Yuja won't shy away from being a virtuoso not just because she’s young and energetic but because she believes that she can make an immediate connection to her audience through virtuoso works. But above all, what she wants to bring to her audience is musical enjoyment.

- With about 100 yearly performances, Yuja spends most of her time in hotels, concert halls and airports. She maintains an apartment in New York one street behind the Carnegie Hall. She usually takes two days of rest there each month with always a second suitcase packed and ready to go. The thing that bothers her most is airport security, particularly in New York which treat everyone as terrorists.

- Yuja’s mother always counts the days until she can see her daughter again. Since being recruited into Curtis, Yuja hadn’t returned home for three years, did so once in 2007, again disappeared in 2008 and then came back this Chinese New Year. Even when Yuja is in China, she’s always busy giving concerts. Her mother complained about her low-cut concert gowns and wanted to take her shopping. Yuja rebuked jokingly, "Stop moaning or I’ll take everything off," revealing the American rebel in her. [I suddenly realized that if you combine the two Chinese characters Yu 羽 and Ja 佳, it forms her mother’s family name Dyi 翟.]

- Many classical labels including Decca, Sony and EMI have tried to sign her but Yuja has fallen for the yellow label since listening to a Chopin recording by Pollini. She didn’t know that the yellow label executives had followed her European appearances for a whole year until Michael Lang, president of DGG, invited her to sign an exclusive contract the day after listening to her at the Verbier Music Festival in Switzerland.

- Yuja’s future plan is to further her studies in European history and culture and to redistribute her concert commitments to give more time to Europe, Asia and China. She hopes to give at least 5 Chinese concerts per year.

To conclude, I’ll quote from conductor/pianist Michael Tilson Thomas when he introduced Yuja to the audience in Carnegie Hall: "(Yuja) has touched my heart with incredible seriousness and depth in her music making, at the same time she has such a sense of fun, adventure and everything new."

That's precisely the same reason this CD merits our Blue Moon Award. |

|

|

|