This review page is supported in part by the sponsors whose ad banners are displayed below |

|

|

|

|

|

Often it comes down to balancing between technical imprecision and great performances. The legendary golden take of a musician is defined after all by not being repeatable. Of course there are some practical basics by which a good performance becomes more likely. One that’s often overlooked is the monitoring quality. Be it during playback fixes or original all-thru capture, it is essential that each instrumentalist or vocalist hear themselves and the others well. ‘Well’ goes beyond just sufficient loudness. The relation of vocals to main instruments and overall performance level determines whether the singer seems to yell or hold back, even get subdued.

Again, it’s a multi-layered process which requires serious expertise just to record some music. And there’s a lot more to it still. In 2014, music production enables manipulations which just a few years ago would have been wild dreams or magic alchemy. In many music genres—even those where you’d not expect it—it’s become standard MO to edit extensively. The goal is perfection; or whatever a given team presumes that ought to mean.

When you consider the timing and pitch errors one hears on classic albums by the Beatles, in particular the Rolling Stones and The Who but also Pink Floyd’s legendary audiophile chestnut The Dark Side of the Moon, one feels confident that all of it would have been edited out for a 2014 production. For a long time edits were limited to gluing together successful parts of a song. And gluing is no euphemism but literal fact. The tape was cut with razor blades and patched together with glue.

|

|

|

|

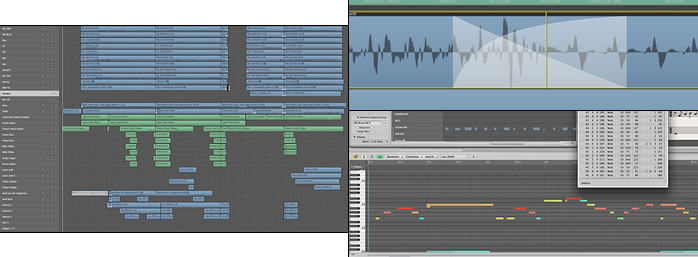

song arrangement showing certain splices (vocals at the bottom) | crossfade upper right, MIDI editors lower right

|

|

MIDI, sampling & Co. During the 1980s MIDI revolutionized broad sectors of the recording industry. Subsequently it was possible—particularly with keyboards—to record pure command data rather than actual sound. To put it simple, a so-called sequencer registers which key is pressed when, for how long and how strongly. Those data are pure numbers. To define pitch, a scale of 0-128 might represent the number of possible tones. Here one restriction becomes self-evident. A trombonist for example can decide long after starting a tone which pitch he means to end up with. At least theoretically he has unlimited options since unlike with a piano, his pitch isn’t fixed. It’s nearly impossible to clone a perfect trombone with MIDI.

But with MIFI it is child’s play to replace a wrongly touched key during an otherwise stunning solo by 'bumping it' to the correct key. With a sequencer program that’s just one mouse click away. Ditto for finger pressure. That’s simply a value from 1-127. But there’s more. A sequencer remembers each command input’s musical timing. This allows for very comprehensive alteration beyond basic time shifting to affect a groove. After all, it’s often not the metronomically precise beat keeping which has a song soar. Often it’s the slight delays or early beats which in tandem with loudness changes create what we call groove. One can even stamp a groove's time signature of one recorded track onto others. If a song is slightly too slow or too energetic or requires an uptick of acceleration for the refrain; or if the fundamental key is a problem for the vocalist: no problem, all of it is variable.

Clearly the sound generation in MIDI is artificial but today’s best system have gotten so advanced that distinguishing fake from authentic instruments can become challenging even for musicians and experienced sound techs. So-called sampling is based on actual sounds, their articulation, finger pressure, air speed and such to clone for example a Bösendorfer grand piano that was played in a first-rate acoustic.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today’s samplers no longer are discrete components but plug-ins, i.e. specialty programs which embed in basic software. For intuitive reasons sampled instruments are used more often that you’d think. Don’t worry about pure classical recordings yet but do read the small print for film scores. A Hollywood scoring with authentic orchestra could cost more than the entire budget of a German independent film. On occasion music production is a game of legos where pre-fab parts like repetitive phrases of instruments or vocals are combined. Too often music is simply a product whose creation can’t rely on the romantic notion of a genius composer and full symphonic or other forces.

What started with the splicing of analog tape too has climbed the evolutionary ladder. Today’s DAW systems enable non-linear non-destructive manipulation of the recorded signal. One no longer cuts an analog tape (which in the worst case was destroyed in the process) to leave the original data untouched. The DAW is simply instructed which part of the audio data to play back where and when. Now it is possible to compare a challenging chord change in the commercial recording which occurs multiple times over in a song. With just a little training one can recognize whether a player repeated himself with unusual precision naturally or whether one really deals with a carbon copy splice instead. Pay attention to that during your next listening session.

|

|

|

virtual instruments |

|

One can also detect audible seams. It’s sad to hear what the limited per-job time and short-lived appeal of certain radio programming tolerates. The otherwise lovely Nobody’s Fault but Mine of British singer Beth Rowley suffers from splice crackles during her solos. |

|

|

|

|

A few minor mistakes would likely have been more sympathetic but all of it serves as a reminder that artistic expression and listening pleasure are bridged by a lot of trickery. To arrive at inaudible seams requires proper matching of spliced materials (particularly on the radio one often hears unnatural changes) which reach deeper into our box of tricks. A common solution is the crossfade which over a few milliseconds connects two sections. The position, length and particularly curve shape of the fader all make for often difficult work.

The advantages of MIDI relative to carelessness with pitch and timing did stay clear of audiophile productions for a while but over the last ten years much has changed. Today it’s possible for example to correct a slightly out-of-tune tone without leaving marks. In fact even performers with horrendous intonation can put their name under a production without lying (and, surprisingly without any shame, claim how "that’s what modern recording tech is there for, ain’t it?").

|

|

|