This review page is supported in part by the sponsors whose ad banners are displayed below |

|

|

To take advantage of its fully balanced circuitry, I configured a setup with AURALiC's 200-watt Merak monos and my 85dB inefficient Albedo Audio Aptica. Given the amps' low 2.2V input sensitivity, I had to operate in the Lindemann's last 10 digits of its volume range. I didn't have sufficient gain. The matching Vega DAC's 4Vrms output did better but with these ceramic transducers, class D amps and no pre, the Lindemann in particular sounded just a bit anaemic and uncommitted. Not wishing to complicate things with a preamp, I went for the Job 225 instead. Though this meant reverting to unbalanced, it also netted 35dB of gain and a high 0.75V input sensitivity. Being a very wide bandwidth DC-coupled circuit, this neutral amplifier also wouldn't downplay potential direct-drive issues which the musicbook:15 and AURALiC competitor might exhibit.

|

|

|

|

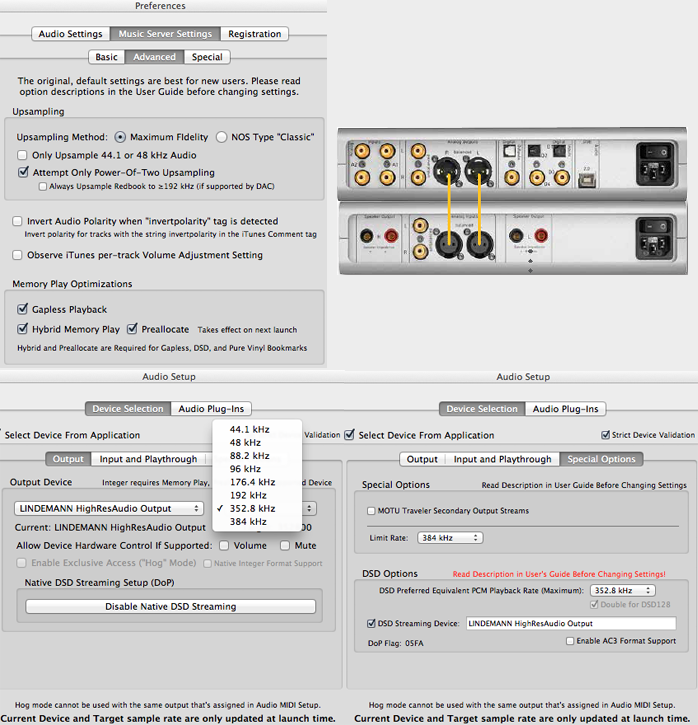

With the Job 225, the musicbook was down by 20 on the gas. This meant ~75 with sufficient headroom to do the nasty. With the Vega, I'd dropped to below 40. This meant early bit decimation on its digital volume control. Even so, both converters were far more alike than not. Versus my fixed-out Metrum Hex, the AURALiC has always been the glossier player. It paints in saturated Technicolor and creates more sumptuous coddling where the Dutch's ace card is trim timing à la Brit PRaT. Now the musicbook took sides with the Hong Kong deck. As my headphone rounds had previewed, Norbert Lindemann too likes his richer deeper colours. On that count I heard a draw with the Vega. Where I perceived a minor difference was on transient prickliness. The Vega was a bit rounder and more viscous. Be it on Rafael Cortéz's Flamenco guitar apoyando and golpe execution or Jacques Loussier's right-handed piano work, the Lindemann borrowed a bit from the Hex. On overall sonics however, the musicbook:15 was far closer to the Vega - not a complete overlay but close enough to play stand-in. |

|

|

|

The bit I hated about the German as preamp was its very narrow IR acceptance window. My source gear is placed on the sidewall toward the right speaker. Aiming at the Lindemann from my seat fired blanks. I had to get up and stand pretty much in front of it before the wand would respond. For volume control, infrared from my seat was utterly useless. If your rack sat between the speakers, you'd obviously be in business; and Lindemann's display is terrifically legible and crisper than AURALiC's. My layout simply produced no remote joy.

|

|

|

That said, with the musicbook's analog volume control, there's no worry about bit decimation or de/re-modulation to pure 1-bit mode of DSD signal*. What did I think of amp-direct mode? Surprisingly effective. With the Italian ceramic speakers, I deliberately acquired a counterpoint to my solid-wood soundkaos and Boenicke transducers for a very different flavour. The Swiss speakers emphasize tone and textural redolence. The Italians major on extreme articulation with full treble illumination. The former are quasi vintage, the latter ultra modern. Whilst DAC-direct drive didn't move the Aptica into tonewood country, at standard levels it also didn't default into the overly lean or whitish. Only at rather low volumes would I personally favour a fat injection with a suitable preamp. Of course forcing a speaker from one sonic school to behave as though from another is silly. But in the end it's always about the right balance between polarities. For my tastes, lower SPL and this speakers, I'd favour the additive qualities of an appropriate preamp; or a warmer lusher amp than I had on hand at the appropriate power rating. On the plumper thicker Wave 40 ovals which are soft on top; and the Boenicke tykes on spikes with their long-throw sidefiring mid/woofers - I'd skip a separate preamp, keep it simple and enjoy more vigorous translucent sound.

|

|

Here's how the designer of the PS Audio DirectStream DAC explains how they apply digital attenuation to DSD: "It's false that applied math isn't possible on DSD but it's true that you can't keep to one bit during all of it. That's true too for PCM. If you take a 16-bit PCM stream and never apply more than 16-bit math, you can't adjust its volume effectively either. You must allow yourself higher precision for intermediate results in any kind of DSP or lose most of your accuracy quickly. If you just chop back to 16 bits afterwards, you also lose accuracy. You must dither back to 16 bits to keep accuracy. Our DSD math keeps high precision up to the end where the signal is remodulated to 1-bit. DSD remodulation to a lower bit width is analogous to PCM dither. They are both ways to keep more essential information about the audio than you would otherwise expect for a given bit width" [from an email exchange with Aussie contributor John Darko].

|

|

|

|

|

As Norbert Lindemann had promised, his circuit proved very responsive to 24/352.8kHz DXD and DSD128 tracks. Of course the few I own were provided by audiophile labels for demo purposes. They represent best-case and nearly unfair scenarios. But despite such a rigged game, it still was instructive to note the descent of weight on recorded ambiance. Rather than spiderwebby hints, with such files the sense of foreign space behind the speakers—clearly other than my own acoustic—was more profound and material. The second benefit particularly with DSD files was a calmer more laid-back gestalt as though a certain amount of stress had been bled out. Together it added up to richer mellifluousness. This ability to distinguish flavours between PCM and DSD formats and their various data densities was more pronounced than over the Vega DAC. This might have been due to the way the AKM silicon treats these formats truly discretely.

|

|

|

|

|