This review page is supported in part by the sponsors whose ad banners are displayed below |

|

Act III: Headphones in the big rig. Crossfeed blossoms into headphones. And just as with real flowers, there's a season for it. After running through my resident Yamamoto and Woo valve machines, I noticed how their superior tone density and portrayal of connective inter-note tissue made some of the StageDAC's between-the-ears contributions particularly in the blend/fill mode less apparent. Let's quickly visualize the process. To place a recorded signal between the left ear and stage center, some right-channel signal is required to move the sound's apparent origin out of the left ear towards the right. The louder the right channel, the farther the apparent sound source travels towards it. At equal output from each channel, the sound is dead center exactly like mono. As the right channel plays louder than the left, the sound source moves right until finally only the right channel plays and the performer seems inside the right ear or speaker.

|

|

This is stereo 101 but we often forget how headphones caricaturize some of this action by isolating each channel from the other. Crossfeed in the headphone setting fills in the virtual stage from the middle towards each ear. The stage gets denser. This doesn't happen like valve-sourced 2nd-order distortion which texturizes everything. Still, things become a bit more corporeal. To isolate these crossfeed effects from harmonic distortion effects, I eventually gravitated to the KingRex Headquarters' transistors to get a better fix on these phenomena.

|

|

Very simply, the two crossfeed options represented by the above icons left and center for headphone and speaker use (right is bypass) act as image density shifters. They quite effectively redistribute image density.

All four of my top headphones latched on to this but when it came to crossfeed wide (the central icon setting), Sennheiser's HD800 took the lead in maximizing the effect, perhaps because they already stage more broadly than most.

Just how potent these effects were relied directly on what was encoded on my software. Even something as apparently simple as a Gladiator track with ominously low ostinato string tremolo and drum whirls over which rises a plaintive lone duduk could noticeably stretch laterally due to how it was recorded.

As an original soundtrack meant to underscore visuals of epic scope, this expander action was supremely enjoyable and very effective. A sudden flick of a switch however could collapse it again should puritanical notions forbid such pleasures. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

The peculiarity of this approach was its apparent randomness. If you move your speakers another 2 feet apart, your soundstage will be wider on all music (even though differences from recording to recording naturally remain). With crossfeed, certain tracks will be obviously enhanced, others not at all and many only to very subtle degrees. Those that stand the most to gain are, not surprisingly, massive orchestral spreads. With them, the virtual stage is densely populated not just center (solo vocalist) and back left and right (piano and drums) as it would be for small Jazz ensembles. Instead, it is stacked solid wall to wall like a tower of sardine cans turned sideways. That's where the blend/fill mode comes to the fore most. Naturally, listening to large-scale classical over speakers in a normal living room already stretches credulity. Such rooms would barely accommodate a woodwind quintet. By the time the oceanic scope of a full 80-head orchestra is shoehorned into 10 skull inches across as it is with headphones, the hyenas of ridicule start cackling. That stated, one could argue that particularly for such need-all-the-help-they-can-get occasions, crossfeed becomes plain mandatory. This I wouldn't challenge.

When obvious, the wide setting expands the virtual stage laterally. At times, this effect sounds more phasey or dithery than others. The fill setting increases density between center and sides but leaves the outer stages edges alone. Mono-fixed information remains completely unaltered. On recordings with a high degree of audible space or recorded ambiance, the fill setting can introduce a subtle blur particularly at the higher values of time delay and amplitude. On piano recordings in particular, slight tonal balance shift can enter listener awareness but be tweaked with the two correctional contours. All this depends directly on the musical material. Hence it's meaningless to get more specific. Suffice it to say that unlike the D/A conversion options whose audibility is very minor, Jan Meier's crossfeed—under applicable circumstances dictated by the software—is not. I remember experimenting with HeadRoom's equivalent processor only to feel more or less frustrated by my inability to notice it. The StageDAC's implementation is a knife that clearly cuts. As such, it works exactly as advertised. On headphones. Particularly with classical. On speakers, I really found it superfluous altogether.

|

|

|

Act IV - As big-rig DAC over loudspeakers

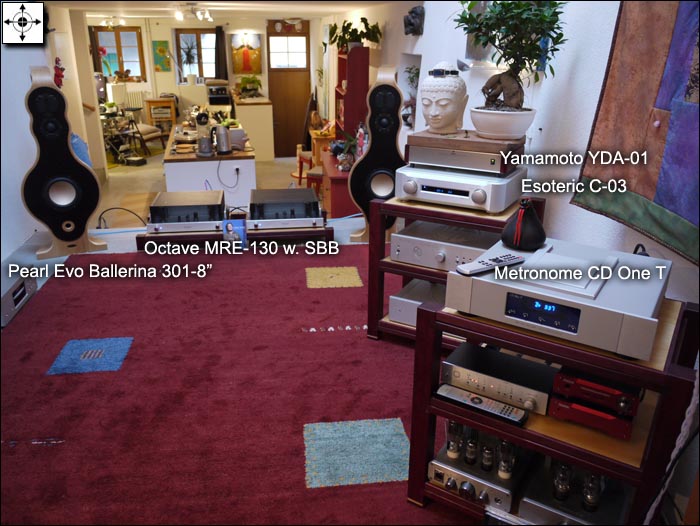

StageDAC/Yamamoto: Confirming that neither crossfeed nor filter settings had any substantial effects in this context, I focused on assessing the StageDAC's converter performance via its fixed output in comparison to my customary Yamamoto YDA-01. The modified Philips CD-PRO2 transport in the Metronome ran spin duties. 1s and 0s traveled to either converter via Stealth Varidig. All other cabling was Acoustic System LiveLine.

|

|

The significant price difference could (should?) have made this a foregone conclusion perhaps but audio has its share of nicely contrarious surprises. Not this time though. While soundstage scale and subjective distance to the listener were comparable, the Yamamoto had the far more potent tone colors and stronger bass grounding. In general, there was overtly more meat and substance on the musical skeleton—one tends to suspect its far beefier power supply—than the Meier which felt more ethereal and removed. While the Swans ribbon tweeter in the Italian Pearl Evo speakers is surprisingly well behaved, high levels and close-mike'd piano for example can get brittle and glassy sooner over it than with my customary soft dome Dynaudio Esotar clones.

|

|

Similarly, the Meier DAC reached this zone sooner than the Yamamoto when output levels and harsher recordings conspired against it. The Japanese DAC's deeper color temperatures and tone saturation withstood software-induced counter trends into lean and edgy rather longer before they too capitulated. Feeling at this juncture that a comparison to a thrice-priced machine wasn't particularly useful to prospective buyers, I moved April Music's Stello DA100 Signature into position. That's priced competitively to the Meier to furnish us with a relevant conclusion. How does the StageDAC compete against a well-liked and known quantity in its own price class?

|

|

|

|

|