This review page is supported in part by the sponsors whose ad banners are displayed below |

|

|

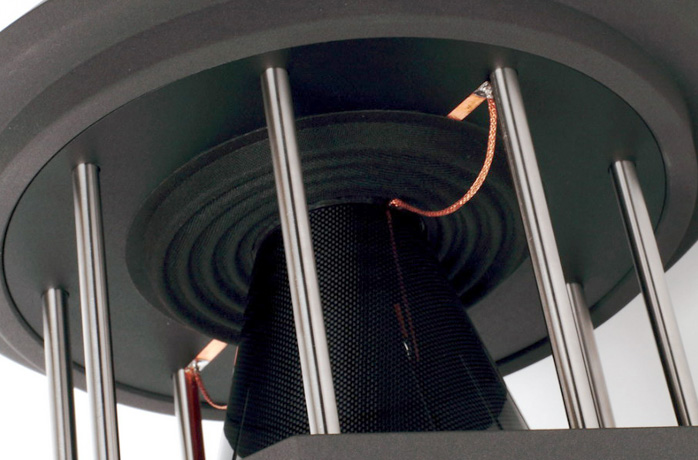

The German Physiks HRS-120’s unorthodox look is the first clue that it is unlike other speakers. The driver on the top of the cabinet is our DDD, proprietary to German Physiks and to be regarded as the heart of the design. The same driver is used in all our speaker models. The DDD was developed by German engineer, mathematician and sociologist Peter Dicks. |

|

| |

Robert Kelly at left, Harald Knoll, designer of the HRS-120 at right |

|

|

|

|

|

|

In 1978 he began to investigate certain fundamental problems of loudspeaker driver design. He was particularly interested in the Walsh driver designed by the American engineer Lincoln Walsh and used in the famous Ohm F loudspeakers. To assist his research, Dicks developed a computer model to describe the behaviour of this driver. He then spent several years building and testing prototypes of an improved driver and refining his computer model until eventually he had produced an extremely impressive sounding new design together with a complete theoretical model of its operation. The new driver had a very wide operating bandwidth, comparatively high sensitivity and was physically rugged. The latest version uses a carbon fibre cone, which is relatively immune from the attention of straying little fingers and those doing a bit of over-zealous dusting. Dick’s driver came to the attention of Holger Mueller, the owner of a German loudspeaker company called Manhattan Akustik. Mueller was intrigued from the start. He was himself the owner of a pair of Ohm F loudspeakers and always believed that the Walsh driver had enormous untapped potential.

|

|

He agreed to license the DDD driver and formed German Physiks to develop the design. Two more years were spent further refining the DDD before it made it its debut in the first German Physiks loudspeaker, 1992’s The Borderland. This model is still in production today though by now in its Mk IV iteration. It is from this model that the HRS-120 was developed.

Although the DDD driver bears a superficial resemblance to a conventional pistonic driver with both types having a cone, voice coil and magnetic circuit, how the DDD driver operates is rather more complex. At low frequencies the DDD driver works like the pistonic drivers in conventional designs. Then pistonic operation is progressively replaced by bending wave operation. The cone on the latest DDD driver is made from a 0.15mm (0.006 inch) carbon fibre sheet, which is very flexible and the termination of the cone is much stiffer than in a conventional driver. Consequently if the voice coil acceleration is sufficiently high, instead of the voice coil and cone moving uniformly together the carbon fibre bends and a wave travels down the cone wall toward the open end. This is referred to as bending wave operation.

|

|

At the frequency where a standing wave is established on the cone wall, the cone goes into break-up and then the sound energy is radiated using modal radiation. You can imagine this as vibration patterns on the cone surface much like those when a pebble is dropped into water. A more detailed description of how the DDD driver works is available on the German Physiks web site. The use of use of these modes of operation provides two important advantages.

First it gives the DDD a very low moving mass and consequently an exceptional transient response. This is easy to hear in the life-like snap that percussion has reproduced by the HRS120. There is no sense of dynamic compression. With sufficiently fast electronics like Spectral, transients can make you jump even when you know they are coming. Second, it allows a very wide operating bandwidth. In the HRS-120 the DDD operates from 240Hz up to 24kHz and thereby avoids the need for the crossover point in the midrange commonly found in conventional multi-way designs. This gives a very significant improvement in overall clarity as our hearing is very sensitive in the midrange and anomalies here are most easily heard. The consequent purity of the midrange combined with the DDD’s high degree of phase linearity enables it to very accurately reproduce the timbral characters of the instruments in a recording.

|

|

|

Another feature of the DDD is that it is very transparent and maintains this transparency at all signal levels. When you play back complex high-level passages of music, you will be able to follow all the threads of music rather than being presented with a confused mixture. A happy consequence of the DDD’s construction is that it radiates omnidirectionally. This more realistically recreates the type of sound field one would experience in a live performance, where most of the energy from a broad range of frequencies is reflected before it reaches your ears. This also means that the timbral balance of the sound is much more even throughout the room than is possible with conventional drivers due to their tendency to beam at higher frequencies. In addition, the exceptionally well-focused and realistic stereo images that the DDD produces can be enjoyed from a wide range of listening positions in the room. This makes it much easier to share the enjoyment of your favorite music with friends and also helps to make listening more relaxing as you do not have to worry about staying in the small sweet spot that most conventional designs produce. It can also help to prevent marital strife.

|

|

The simple looking cabinet conceals a few clever ideas. Most of its volume is taken up by the bass system. This consists of a sealed enclosure with a downward firing 10-inch woofer fitted at the bottom end. This covers the range from 240Hz down to 29Hz. The energy from this system emerges from the openings at the base of the cabinet so the low frequencies are radiated omnidirectionally to match the radiation pattern of the DDD. The use of an octagonal cross section for the cabinet means that individual panels are smaller and therefore stiffer than panels of a square section cabinet of the same volume. Stiffer cabinet panels vibrate less. Vibrating cabinet panels can severely degrade the performance of a loudspeaker system. The only things we want vibrating are the drivers and your feet.

|

|

To minimize residual panel vibrations, a special damping material called Hawaphon lines the inside surfaces of the cabinet. Hawaphon is a polymer sheet containing a matrix of small cells filled with very fine steel shot and was originally developed as an anti-surveillance measure for military and government buildings. It adds mass to the cabinet to reduce the resonant frequency and the ability of the shot in the cells to move against each other provides a very effective way of converting vibration energy into heat. Hawaphon achieves broadband attenuation of structure-borne sound of better than 50dB.

The HRS-120’s cabinet has a small footprint, talking up just over a square foot on your floor.

|

|

This is more impressive when you hear the quality of the bass in terms of depth, speed and control and how loud it can play. However, when it does play loud, it maintains the delicacy, detail and finesse it shows at other levels. One more useful feature of the HRS-120 is that it is not overly critical of room positioning. Like all loudspeakers it will benefit from extra time and care taken in fine tuning but a good sound can be quickly produced without the need to adjust the position to the last fraction of an inch. Being an omnidirectional design, you also never have to adjust toe in.

|

|

|

|

If I may, I would like to add a few subjective comments about the sound. In nearly 25 years in the audio industry in both the professional and high-end sectors and having worked in the UK, USA and Japan, I have heard a lot of loudspeakers. Many were good hifi but very few were exciting on an emotional level. Music is fundamentally an expression of emotion and without it music lacks meaning. With their transparency, speed and sheer musicality, the German Physiks designs manage to reproduce that essential emotion. I have lost count of the number of hours I have spent listening to music on my own set of HRS-120s when I should have been attending to urgent jobs but they drew me into listening to just one more track.

Robert Kelly

German Physiks, manager |

|

|